A Blueprint for Housing AND Climate

Solving for Canada's housing crunch in a climate smart way

Yesterday, the Task Force on Housing and Climate released our findings on solving Canada’s housing crunch in a way that won’t make our climate challenges worse: the Blueprint for More and Better Housing. (Some nice coverage here and here at the 1:06:15 mark.)

Let’s start with the hard fact: Canada need millions more homes. We need to double or triple our production in the coming years to restore sufficient supply and vacancy for the market to work properly again.

But let’s humanize this issue: my kids will need their own housing soon enough. Our parents will need different housing as their needs change. Newcomers essential to our growth need better housing now. People who are barely making rent today need better options to live closer to school or jobs. And our fellow Canadians who are unhoused are most acutely in need of shelter. Our housing challenge is an economic problem, but it is also a social problem, and our cities and towns are fraying because of it. As Co-Chair of the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, I am of the view that homelessness is a housing problem. So, as we argued in last summer’s Housing Accord, we need to get building.

We are also finding out the hard way that our existing housing stock is not as resilient to our changing weather as we might like. Canada is warming at twice the rate of countries at the equator. It’s even more harsh closer to the poles, which is why we started working on climate adaptation in Edmonton (53 degrees north) over a decade ago after we noticed thunderstorms becoming more severe . Now extreme weather is showing up across Canada in floods, fires, heat domes and bad air. A decade ago, almost nobody had air conditioning in Edmonton, and we didn’t think twice about what kind of shingles to use. This summer I spent time this summer hacking together air filters because of record wildfire smoke. And the city’s water utility works valiantly to overhaul our drainage system to deal with overland flooding. The change is upon us.

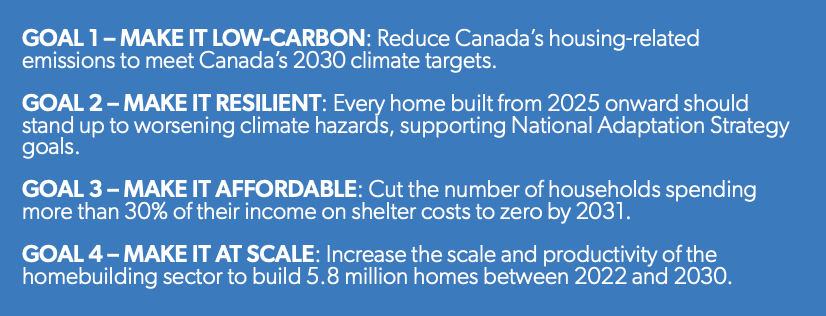

So how do we build those millions of needed homes, make them affordable, and deliver them in a way that doesn’t make our climate challenges worse? These are the goals the Task Force set out to solve for:

But to work the problem, it helps to try to understand how we got here. This is my analysis, not necessarily the Task Force’s, but it reflects issues we examined on our way to our 140 recommendations to local, provincial and federal decision makers.

Canada is far from the only G20 nation with a housing crisis, so we didn’t do this to ourselves, at least in the convenient way that there is a villain or a cabal who can be held responsible. These are classic wicked problems with complex causes, and they deserves serious consideration at the systems level if we are to actually solve them.

The cities we’ve built in Canada, and the majority of our growth since the Second World War, was easy because we had plentiful cheap land, (mostly) cheap energy, abundant labour and cheap materials at hand. The input costs for infrastructure and buildings were astonishingly low compared to today. And so we built up and spread out, and homeownership was made attainable for many. Then, one by one over the last decade, those tailwinds shifted: speculation drove up land values, concrete and steel became more expensive, lumber prices became more volatile, energy costs rose, plus an aging and shrinking skilled work force created a perfect storm for constrained supply of inputs, even as demand for housing surges.

The economics of Canada’s systemic housing market crunch further deteriorated over time through commodification and financialization of housing, and asset appreciation facilitated by historically cheap borrowing rates. These financial conditions collided with restrictive regulations about how much can be built which has indeed constrained supply. Then, somewhere between the pandemic and tragic geopolitical upheaval, we reached the end of decades of extraordinary price stability, prosperity and growth that somehow made it all still work, at least for middle income folks. Then, in more and more of our cities, the housing market stopped working for most people.

Or failed, if you prefer.

Many renters and people on fixed income have been feeling this supply crunch for years as the rental stock aged and shrank relative to population growth. The federal government’s decades-long multi-party absence from the non-market housing space (until recently) exacerbated the crunch for those with the least means to pay. We are at least a million units short in the non-market/supportive/community/social part of the housing spectrum, which is both a contributing factor in rising homelessness, and a vexing barrier to solving it quickly.

This is the world we live in now. Things are ever more constrained, and scarcity breeds anger and contempt better that it breeds solutions. But like any constraint exercise, these conditions invite creativity and force prioritization. As the Task Force pondered all these challenges, it turns out where we build, what we build, how we build and why we build are the key questions to answer.

Where we build led to two strong conclusion. First, we must legalize density, particularly near existing infrastructure, services and jobs. Eliminating parking requirements, increasing opportunities for small apartments and for secondary suites on all sites will help. We must also stop building in high risk areas like floodplains and in wildfire prone areas. We can’t afford to waste houses by having to repair or replace them after predictable losses.

What we build got us thinking about adopting stricter building and safety codes. We need to adopt the highest energy and safety standards now, and revisit the code more often while streamlining it to deal with changing climate vulnerabilities. Making sure these homes can stand up to the weather over the next century is key, otherwise their owners will struggle to find affordable insurance, and experience more costly loss and disruption. Energy efficient buildings are cheaper to run, inefficient buildings undermine our emission reduction goals and contribute to hidden costs and energy poverty. Stricter building codes are needed to protect those structures, and the people who live in them. This is necessary safety and consumer protection regulation. Some will argue this will add cost to homes, but so do seatbelts and catalytic converters in cars. In the big picture we simply cannot afford as a society to build millions of maladapted homes. This it would be negligent to slow walk code updates now.

How we build needs to evolve to leverage Canada’s manufacturing know-how to deliver more factory built-housing. We still hand build most housing in place, outside, in Canada. Is it any wonder they cost so much, and take so long? In Sweden, more than half of housing is built at least partially in a factory. Tooling up factories, hiring specialized labour, and securing supply chains is hard, and there have been many failures in this boom-and-bust space. So we have specific recommendations about tax measures and industrial policy to support scale up. It’s worth persevering on this to realized inheret efficiencies, speed, and the all-elusive productivity gains our economy needs. Frankly, I can’t see how we reach the kind of production velocity we urgently need without much more offsite panelized and modular construction.

And why we build is back to where I started. Everyone needs shelter in a winter country. Without stable housing, people struggle and their health deteriorates. Their families face more stress, their productivity is impacted. And precariously housed and unhoused people experience more violence and exploitation, and are more exposed to heat, smoke, and other rising climate-related vulnerabilities. This is untenable for everyone losing sleep about their housing situation in Canada.

The need is so significant that the Task Force believes 2.3 million below-market and non-market units are required, based on a soon-to-be published needs assessment. This can be achieved through acquisition and retrofit of the existing stock (faster and cheaper), along with new construction of dedicated community and supportive housing, as well as long-term below-market affordable units delivered with the scale of applied private sector capacity and partnership. There is a strong role for public lands in this goal, and the Task Force calls for creating a public land bank and bringing financing and tax measures to the table to deliver more non-market and below-market homes.

I have to believe we can still accomplish great things in this country, and especially at the local level. I’ve seen at least part of what it will take in the work we did in Edmonton over the last decade. Several consecutive City Councils worked to streamline zoning rules, cull formulaic requirements like parking minimum ratios, and make the process easier to navigate for builders and investors. We are still completing some newer neighbourhoods, but at much higher densities than before. Taken all together, the dream of home ownership is still alive in Edmonton. Here’s an excellent explainer video of how we legalized density, and what is being built already.

Sadly, as the video notes, our community’s work to end homelessness is facing incredible headwinds after successfully reducing it by over 40% between 2009 and 2018, so that unmet need for supportive housing at the acute end of the spectrum remains vast here and in cities and towns across Canada. But just imagine: what would things would be like if the City hadn’t delivered thousands of affordable homes since 2018, and if Edmonton’s agencies hadn't housed over 16,500 unhoused people since 2009?

I can attest, this is all hard work, and it takes time and perseverance. But our kids and our neighbours deserve housing that is affordable to own or rent, housing that is cost effective to heat and cool, and that is safe from reasonably predictable disasters.

Surely we can all agree on that?

It should be said, there is no single Premier, Mayor or Prime Minister to blame for all this. Fixing our housing crunch does not depend on heroic leadership by one order of government or one worldview over another: it will take leaders in all spheres, and of all stripes coming together, as the Task Force has tried to do. The Blueprint, crafted by finance experts, former public servants, conservatives, progressives, building scientists, designers, planners, builders, academics, advocates, and insurers shows that we can find common ground and coherent, practical solutions.

Through this project, I’ve also been inspired to learn more about extraordinary leadership from Indigenous governments and housing organizations. Climate resilient, net-zero projects like Squamish Nation’s Sen̓áḵw provide member housing and affordable rental within a large market rental development, which manifests every tenet of the Task Force’s ambition. Our Task Force included Indigenous experts and engaged Indigenous groups to learn about what’s working and what’s in the way, but we did not presume to make recommendations to self-determining First Nations, Inuit or Metis governments. However, we do believe a big part of our housing answer in Canada must involve all orders of government working to support ‘by-Indigneous, for-Indigenous, with-everyone’ solutions (as it was crisply put to me by one Mauri elder from New Zealand at a conference last year).

Lastly, I am grateful to the researchers and experts whose work grounds this report in reality; grateful to the Task Force members who volunteered an enormous amount of effort and expertise over the last six months to craft these recommendations; grateful to Dr. Mike Moffat and his team at the Place Centre for helping pull all this together; grateful for all the experts who reached out and offered input and support for our work; and especially grateful to my Co-Chair the Hon. Lisa Raitt for gracefully leading this group to a Blueprint we sincerely hope folks of all political stripes — and across local, provincial and federal jurisdictions — can rally to implement. It has been a tremendous honour to serve alongside this group of caring, brilliant, passionate, solutions-oriented Canadians.

Please take a moment to share this post with people interested in housing and climate solutions, and share the report with your local, provincial and federal elected officials and ask for their commitment to build on it.

I'd like to see building codes changed to maximize solar capacity on roofs. Why are we still building roofs with decorative peaks, it wastes panel capacity. Had my home builder, built a functional, not pretty roof and lined up all the vents at the peak, I would have been able to place enough solar to meet my homes energy needs. Instead we were able to do 70%. Why in 2024, are we still dilly dallying around? Why aren't building codes already changed to require and maximize all the avenues of efficiency in new builds? Why is this such an uphill battle? Roofs need to be functional, built to maximize solar panels placement, houseing developments need to be oriented for max sun exposure. Eavestrough and window placement should be designed for minimal summer sun exposure, and max winter sun exposure, for cooling/heating purposes.

Are you concerned about another summer of record breaking heat in Edmonton?

Did you know there are basically no protections for renters experiencing unlivable temperatures in their homes?

Climate Justice Edmonton wants to hear how rising temperatures and extreme heat are affecting renters! If you are a renter in Edmonton, please consider filling out our survey about how heat is impacting you in your home. Survey responses will inform a Climate Justice Edmonton campaign that focuses on the rights of renters to be safe, healthy and cool in their homes.

https://forms.gle/YW7T8R4AEFMSmqca6